Review of Declaring His Genius: Oscar Wilde in North America by Roy Morris Jr.

Strange Man in a Strange Land

The Gay & Lesbian Review, Sep.-Oct. 2013

Review of Declaring His Genius: Oscar Wilde in North America

by Roy Morris Jr.

Belknap Press. 264 pages, $26.95

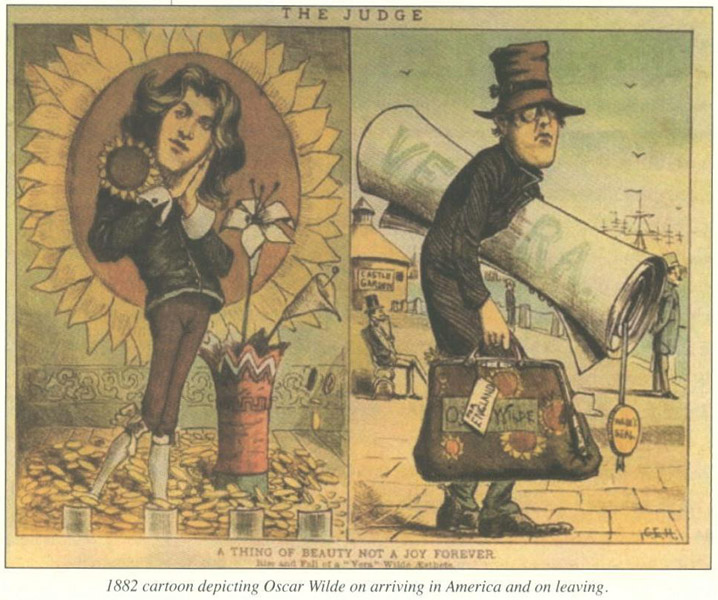

THE TITLE of Declaring His Genius refers to Oscar Wilde’s notorious remark upon landing in New York in 1882 (“I have nothing to declare but my genius”). In this detailed account of Wilde’s year-long speaking tour across North America, Roy Morris Jr., an American magazine editor and historian of the Civil War and Reconstruction, posits that America forced Wilde to grow up: “America had taken the nonsense out of him,” observed a friend. When he returned to London, Wilde got a haircut and declared: “The Oscar of the First Period is dead.” He came to teach Americans to pay more attention to aesthetics, and he learned not to pay so much attention to appearances.

The idea to dispatch the 27-year-old to America was hatched by Richard D’Oyly Carte, the producer of Patience, an operetta by Gilbert and Sullivan, a hit in London that had now opened in America. Patience was the latest parody of the aesthetic movement and featured one Reginald Bunthorne, a ridiculous, flower-wearing poet not unlike Oscar Wilde. But Wilde took the implied criticism in stride. As a beau geste that he would later repeat in New York, he showed up for the London performance of Patience in full gay apparel. Having exported the parody, D’Oyly Carte now wanted to test the American market for the real thing. He explained, “Not only would society be glad to hear the man and receive him socially, but the general public would be interested in hearing from him a true and correct definition of this latest form of fashionable madness.”

His business instinct proved accurate. The plan was a twenty-city tour of the Northeast and Midwest (Wilde’s expenses covered, profits to be divided between speaker and producer). But succumbing to national demand, the tour was repeatedly extended, eventually to include California, the Rocky Mountains, the South, and Canada for a total of 140 cities and towns. The red-eyed speaker delivered lectures lasting an hour or 75 minutes on topics ranging from the English Renaissance to home decoration, to audiences of typically several hundred. The audience in Chicago numbered 2,500. Morris estimates that Wilde made at least $5,600 ($124,000 in today’s money).

Wilde’s journey was a closely watched train—or boat. When he boarded in Liverpool, The New York Times alerted its readers. Before he cleared customs in New York, reporters boarded the steamer demanding everything from a definition of aestheticism to minute personal details. What time did he get up in the morning? Did he like his eggs fried on both sides or only one? “I am torn in bits by Society,” Wilde wrote to a friend just before his debut talk in New York. “Immense receptions, wonderful dinners, crowds wait for my carriage. I wave a gloved hand and an ivory cane and they cheer. Rooms are hung with white lilies for me everywhere. I generally behave as I have always behaved—dreadfully.”

His talks were thoroughly covered, but he received lukewarm reviews. The consensus was that he was a monotonous speaker. But the show continued to sell out. “I was recalled and applauded and am now treated like the Royal Boy [the Prince of Wales],” he wrote to a friend after his debut. “I bow graciously and sometimes honour them with a royal observation, which appears next day in all the newspapers. … Yesterday, I had to leave by a private door, the mob was so great.” In London he’d fought for attention, signing “guest books with a full-page autograph.” In America he was showered with it, sitting down for hundreds of interviews, and was handed requests for autographs, and even for locks of hair.

To he sure, his notoriety made him undesirable in more highbrow circles. Morris notes that none of New York’s 400 leading families came to the talks or the private receptions. But everyone else came. The mayor of New York showed up for a reception, as did dozens of prominent, if little remembered, figures from every walk of life. College students from Harvard and Yale misbehaved at his lectures; Colorado silver miners dozed off while he instructed them about Italian art; ladies wore sunflowers for the lectures; gentlemen dressed up as if for a night at the opera; gay lads (“pallid and lank young men” with “banged hair,” giveaways according to Morris) were reported to be in the audience.

Morris savors the encounters with some of the period’s biggest names. Oliver Wendell Holmes invited Wilde to his literary club in Boston. (Wilde used a letter of introduction he’d brought from London: usually none was needed.) Writer and activist Julia Ward Howe—appalled by the conduct of her nephew, a Harvard undergrad—held a reception for Wilde, wrote to a magazine to call for respect for the visitor, and later invited him to vacation in Newport, Rhode Island. Former president of the Confederacy Jefferson Davis was unfazed by Wilde’s likening the South to independence-striving Ireland. President of the Mormon church John Taylor struck Wilde as “a courteous, kindly gentleman.” Five of his seven wives attended Wilde’s lecture in Salt Lake City. Wilde also met with two prominent writers, Henry James and Walt Whitman. Whitman met him a second time; James found him “fatuous.”

He sometimes complained about the insufficient cultural knowledge of his audience, but does not seem to have dumbed down his talks. His basic approach was to assume that everyone was capable of appreciating art and enjoying beauty. He told the obstreperous Harvard crowd that painting a beautiful picture should qualify for academic credit. Halfway through the year, Wilde boasted that he had spoken to 200,000 people. Morris is impressed by the professional, well-staffed, media-savvy operation. I’m struck by the convergence of entertainment, culture, and mass education.

As Wilde fell into a routine, his wit began to fade. But the press was more obsessed with his opinion of America than ever. How did he find the U.S.? What did he think about the newspapers? How did he like San Francisco, Cleveland, San Antonio? Wilde would utter something along the lines of: “Here in America I find a vast amount of pretty women, and the greatest number I have ever seen together in my life thus far I have seen in Baltimore.”

Morris, echoing the journalists who wrote about Wilde, is likewise interested in Wilde’s opinion of America, but ends with a comment on the latter’s conclusions about Wilde: “Youthful, vigorous, and forward-looking himself, Oscar Wilde found similar qualities in Americans. In turn, many Americans, to their credit, saw beyond the superficial image that Wilde presented on stage to hear and heed the essential good sense of his words.”

Back in London, Wilde lectured about the U.S. and published an essay called “Personal Impressions of America,” which ends thus: “It is well worth one’s while to go to a country which can teach us the beauty of the word freedom and the value of the thing liberty.” For whatever reason, Morris did not quote the sentence that comes immediately before that one: “The Americans are the best politically educated people in the world.”