Review of Arctic Summer by Damon Galgut

What Was Forster Thinking?

The Gay and Lesbian Review, July-Aug. 2015

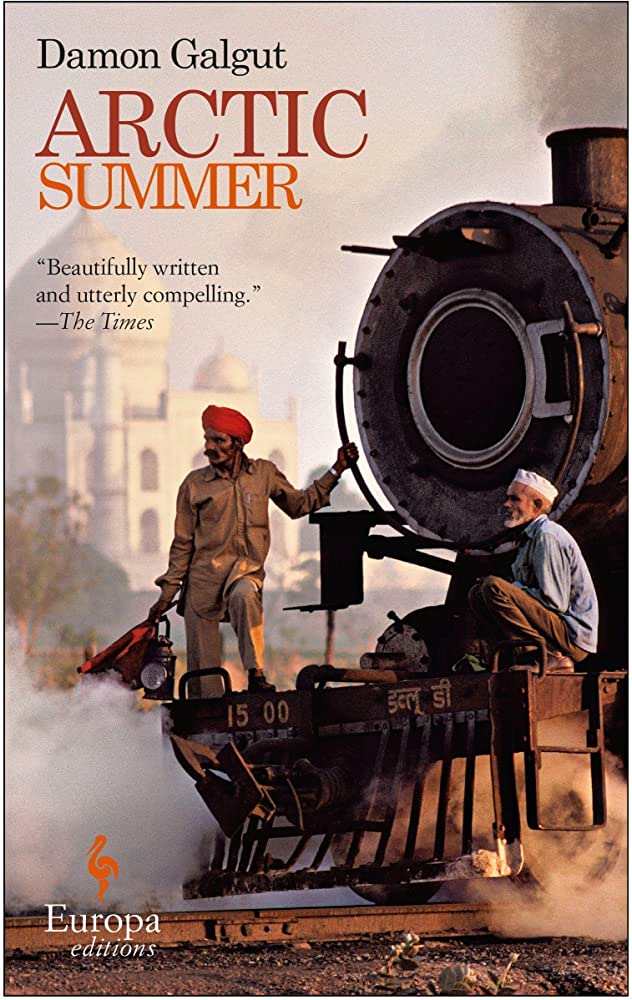

![Arctic Summer [Book] Damon Galgut](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/W/IMAGERENDERING_521856-T1/images/I/91iBhvEj2QL._AC_UF1000,1000_QL80_.jpg) “ARCTIC SUMMER,” the title of an unfinished novel by E. M. Forster, well suits this fictional biography of the English writer. It’s hard to imagine a writer further away from the romantic image of the struggling, mercurial artist. Forster was born in 1879 and died in 1970, at age 91. An only child (a brother died in infancy), he lived with his widowed mother in a London suburb until her death at ninety. He began writing a few years after graduating from Cambridge, and success followed gradually but surely. A legacy from a relative spared him the need to work, making writing a labor of love.

“ARCTIC SUMMER,” the title of an unfinished novel by E. M. Forster, well suits this fictional biography of the English writer. It’s hard to imagine a writer further away from the romantic image of the struggling, mercurial artist. Forster was born in 1879 and died in 1970, at age 91. An only child (a brother died in infancy), he lived with his widowed mother in a London suburb until her death at ninety. He began writing a few years after graduating from Cambridge, and success followed gradually but surely. A legacy from a relative spared him the need to work, making writing a labor of love.

In the telling of the gay South African author Damon Galgut, Forster strives for but never receives much warmth.

“Only connect,” the epigraph of his fourth novel, Howards End, will appear now in a new light as the yearning for understanding of a very lonely man. “His loneliness was now so big that it had become his life,” writes Galgut. Clearly Forster’s homosexuality played a role, whether causing or only exacerbating his loneliness. “He could not refer to his condition, even in his own mind, with too direct a term,” so Forster referred to himself “as a solitary.” However, by his thirties or forties, Forster finally came to terms with his sexuality and grew as a writer and as a man. The novel is set during this period of his life, beginning with Forster’s first visit to India and ending in 1924 with the publication of A Passage to India, his final novel.

The first scene introduces the main themes. In his most daring act of independence to date, the 33-year-old Forster is on a steamer heading for India. A conversation on board with a younger British officer intrigues but also unsettles him. The officer lists his conquests—“almost 40” men and counting—and recites his erotic poetry. Forster travels to India to meet Syed Ross Masood. Six years earlier, he had tutored the seventeen-year-old Indian student in Latin in preparation for Oxford and had quickly fallen for him. Galgut juxtaposes the effusive and confident student with the diffident and reserved teacher and, echoing Forster’s A Passage to India, makes a statement on the disparity between British and Indian sensibilities.

Nowhere is this difference more pronounced than in the use of language. Forster, a master of understatement who hardly utters an unnecessary word, is disconcerted by—albeit susceptible to—Masood’s “baroque voice.” Notably, Masood uses the word “love” freely and theatrically, giving it a generous meaning to express attachment and loyalty. When he tells Forster that he loves him—with “great affection, the real love & sincere admiration”—he has in mind the kind of love that family members extend to one another. However, Forster falls in love in a quite English way: his love is precise, dramatic, and irrational, but also hard to express: “Morgan’s head”—Forster used his middle name—“turned dizzily. But by degrees he detached himself and thought it through rationally. He remembered the other letters Masood had written him, their heightened, heated language. The little contact he’d had with other Indians, through Masood, had taught him that many of them spoke in this way. … The words didn’t mean what they did to the English. The language seemed bigger than it was. And yet, despite himself, Morgan couldn’t help responding.”

In Forster’s coming out to Masood, Galgut brilliantly recapitulates observations from A Passage to India on cultural attitudes toward friendship. Both Forster and Masood are tacitly aware that love means something different for them. Masood thrives on this ambiguity, but Forster must see it coming to a head. “‘I love you as a friend,’ he said, ‘but also as something more than a friend.’” Masood, not unlike Forster’s Dr. Aziz, for whom nothing exceeds friendship, retorts, “I know.” Then: “And Masood had understood; there had been a quick pain in his eyes.”

The Forster that returns to England is more resigned about love. India has seen a “capable other Morgan, who traversed great distances and made decisive choices.” Still, Forster needs now to prepare for a different kind of relationship. A sense of urgency is provided by the suicide of a gay acquaintance, a sense of hope by Edward Carpenter, a radical writer on “Homogenic Love,” who invites him to the countryside cottage that he shares with his boyfriend. Forster works out this more hopeful personal outlook in Maurice, giving his gay love story a happy ending but suppressing its publication. He will show the manuscript to acquaintances—Virginia and Leonard Woolf, among others—but it’s Christopher Isherwood who will publish the novel decades later, after its author’s death, in 1971.

World War I presents an opportunity for adventure. Forster, a conscientious objector, volunteers to catalogue paintings as part of the London National Gallery’s war preparations. Next, he takes a position at a Red Cross hospital in Alexandria and tries to tap into the city’s sexual underworld. (One guide is the gay poet Cavafy.) Thirty-seven and a virgin, he is bent on experimenting with passion. He takes advantage of his power and privilege in his quest for sex. He courts Mohammed el-Adl, an 18-year-old conductor on a local tram. Forster appreciates the sex and intimacy but is left to wonder, years later, upon learning of his lover’s demise: “What could Mohammed realistically have felt in return?”

A second visit to India (the third one, in 1945, is depicted in the epilogue) continues Galgut’s reflections on power and friendship. A mature Forster is asked to serve as a private secretary to the maharajah of Dewas. Forster comes out to the maharajah, who’s officially homophobic, to secure his help in orchestrating a sexual relationship with a barber at the court.

Galgut has said in interviews that he was meticulous about the facts, which he assembled from Forster’s personal writings, four biographies, and interviews. But the emotional storyline he constructs is based on his own interpretation. His is a Forster for whom thinking and feeling are two distinct faculties, for whom sentiments are almost always screened by the rational mind.

In A Passage to India, Adela Quested is engaged to marry Ronny Heaslop, the British magistrate of a fictional Indian city, but in the darkness of a cave gains the clarity to ask herself whether she loves him. Forster tells us that love doesn’t quite make the world go round. This realization also informs Arctic Summer, which succeeds in establishing an intimate connection between the author’s life and his most important work.